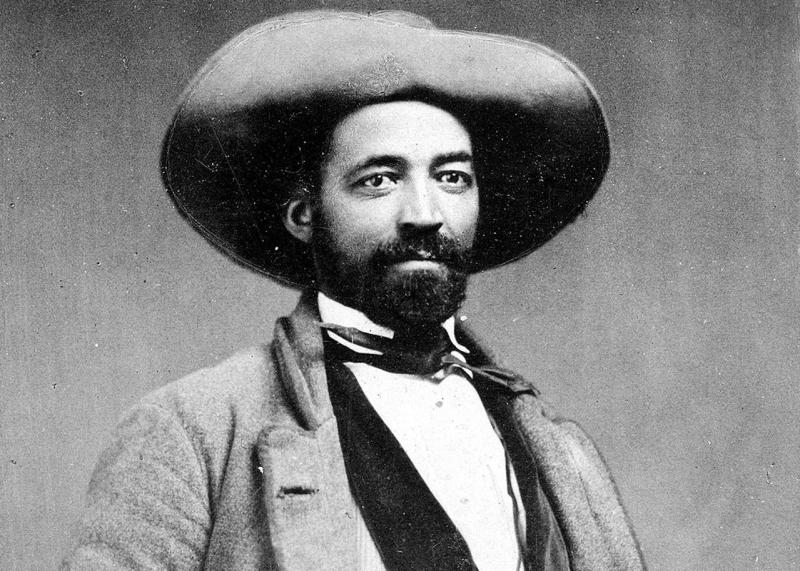

John W. Jones is an essential part of Elmira’s abolitionist history and the definition of Black Excellence. As an agent on the Underground Railroad, he assisted over 800 freedom seekers make their way to freedom. As a sexton, he buried Confederate soldiers during the Civil War and treated each one with the utmost respect. His determination and work ethic made him the wealthiest black man in upstate New York.

I hadn’t heard of John Jones before I visited Elmira, New York where he is revered as a local legend and national hero. Many freedom seekers and famous abolitionists made their way to Canada through Elmira. Despite the unbelievable things John achieved, his incredible story is yet to make history books.

Born June 21, 1817, on a plantation in Leesburg, Virginia, Jones was enslaved by the Ellzey family. He was the houseboy of William Ellzey’s daughter, Miss Sally. As she got older John worried about what would happen to him after she died.

On the night of June 3, 1844, 27-year-old Jones fled Leesburg with George and Charles, his two half-brothers, and Jefferson Brown and John Smith from an adjoining estate. The men walked from Virginia to Elmira, New York. On the first night, they walked 18 miles. The total distance is about 300 miles.

The Underground Railroad route they took went through Maryland where they fought off slave hunters on their way into the free state of Pennsylvania. From there they continued north to New York by way of Williamsport, Canton, Alba, and South Creek. The men took refuge in New York in a barn on South Creek Farm owned by Dr. Nathaniel Smith. They’d crawled into the hay mow to sleep when Mrs. Sarah Smith found the exhausted and hungry men. She cared for them for a week until they could continue their journey. Jones is believed to have been so grateful that after she died, flowers mysteriously appeared on her grave weekly.

John W. Jones arrived in Elmira on July 5th, 1844 with $1.46 in his pocket. Elmira was a major “station” on the Underground Railroad due to its location between Philadelphia and Canada. The completion of the Northern Central Railway escalated Elmira’s contribution to the Underground Railroad. The new railway allowed “passengers” to hide in baggage cars, making their journey quicker and easier.

First Baptist Church

John became the sexton of Elmira’s First Baptist Church in 1847. As an employee of the church, he took care of the property, rang the church bells, kept a record of the church’s dead, and buried them at the Second Street Cemetery. He continued to serve as a sexton for First Baptist Church for 43 years.

Jones became an active agent in the Underground Railroad in 1851. Members of the Underground Railroad often used code words, based on the metaphor of the railway. For example, people who helped freedom seekers find the railroad were “agents” or “shepherds”. Guides were known as “conductors”. Hiding places were “stations” or “way stations”. The freedom seekers were referred to as “passengers” or “cargo” and “Station masters” hid “passengers” in their homes.

Although the Underground Railroad didn’t generally involve trains, it did at John’s “station”. In 1854 the tracks from Williamsport to Elmira were completed. With the help and coordination of chief Philadelphia Underground agent William Still and Elmira abolitionists Jervis Langdon, Simeon Benjamin, Thomas Stanley Day, and workers on the train. Jones was able to hide his “passengers” in the 4:00 a.m “Freedom Baggage Car,” directly to Niagara Falls via Watkins Glen and Canandaigua.

John married Rachel Ann Swails in 1856. They had three sons: John Jr, George Henry, and James Edward, and one daughter Ida Alice. Working as a sexton at First Baptist Church Jones earned enough money to buy a $500 house. It’s endearingly referred to as “the little yellow house next to the church”. It played a vital role in the Underground Railroad. Located along the railroad tracks, Jones’ little yellow house became the perfect “way station” for hundreds of freedom seekers.

By 1860, Jones had dispatched nearly 800 freedom seekers to Canada. He was also a “guide” and “station master” finding shelter for up to 30 “passengers” per night. It’s believed Jones sheltered many in his own home behind First Baptist Church. Of the 860 people he helped, none were captured or returned to the South.

Woodlawn Cemetery

In 1859, Jones became the caretaker for Woodlawn Cemetery. Between 1864 and 1865 he accepted the responsibility for burying 2,973 Confederate soldiers from the dreaded Elmira Civil War Prison Camp. This confederate prison camp received the nickname “Hellmira” for its high death rate.

John was denied entry to two local schools but he fought for his education. His friend Judge Thurston helped him receive one season of formal education. He also found an ally in a 14-year-old boy who helped educate him. This is important because Jones kept immaculate burial records of each soldier by name, rank, company, regiment, grave number, and date of death.

He treated the confederate soldiers, the people who died fighting to keep him enslaved, with care and compassion. Any valuables owned by the soldier at the time of death were carefully cataloged and stored. Each grave was identified with a painted wooden marker.

When Jones saw the name John R. Rollins on one of the coffins to be buried he wondered if this could be the same John R. Rollins he’d known as a boy. The son of the plantation overseer, and whose mother had always been kind to John. He contacted the Rollins family in Virginia and found that their son had enlisted in the army and was listed as missing. Jones arranged for the body to be sent back to the family in Virginia.

When the soldiers’ families received the precious photographs, treasures, and letters that Jones had kept for them, they were so moved that only three bodies were removed for reburial. On December 7, 1877, the US Federal Government declared the burial site Woodlawn National Cemetery. John kept such precise records that the federal government could place accurate headstones on all but seven of the 2,973 Confederate graves in 1907. Both Woodlawn Cemetery and Woodlawn National Cemetery are still active and in 2004 were added to the National Register of Historic Places.

College Avenue Farm

Jones received $2.50 from the government for each Confederate soldier buried. This money enabled him to buy farmland on College Avenue and establish a home for his family. The Jones family home was located directly across the street from Woodlawn Cemetery.

While John was burying the Confederate soldiers his family suffered a horrific tragedy when his three-year-old son, George Henry Jones, died on October 20, 1864.

Between 1847 and 1877 John was the sexton, usher, and general helper at Elmira’s First Baptist Church. Jones and his daughter, Ida, were baptized and became church members in 1878. In 1885 John W. Jones was interviewed by the Elmira Telegram newspaper. He told the reporter “My life, as I look back over it, seems to me a wonder of wonders. Here, I am at 69, but I do not feel like an old man — free, happy, prosperous, at least have enough to eat, yet I was once a slave, and that time seems as if it were but yesterday, so distinctly do I remember the old life.”

At 73 years old John Jones gave up his job as sexton and retired to his farm on College Avenue. However, he did continue as head usher at First Baptist Church and always sat in the back pew. A seating chart from 1895 shows his pew and is a record of his attendance.

John W. Jones died on December 26, 1900, at the age of 83. That’s when locals learned that he was the one who secretly placed flowers on Sarah Smith’s grave weekly. His wife Rachel died on September 22, 1919, at the age of 83.

The Jones House still stands on Davis Street on the original farm property. The small wooden farmhouse is listed on both the State and National Registers of Historic Places. It was transformed into the John W. Jones Museum and opened to the public in 2016.

The museum stands today as it existed in the late 1800s. Walls rumored to be made from the planks from the prison camp, are stripped to their original state. Aged and tattered pieces of wallpaper remain in some areas. One room was restored to what historians expect it may have looked like when the Jones family lived there.

Across the street through the wrought iron gates of Woodlawn Cemetery. John rests peacefully with his wife and children by his side.

Show Your Support

During my visit, Talima Aaron, the President of the Board of Trustees at the John W. Jones Museum shared Jones’ story with me. She explained John’s history but allowed his space to speak for itself. It was an emotional journey through the highs and devastating lows of the Black History. Visiting the home of a man who fled slavery to become a leader, entrepreneur, and national hero gives me hope for the future.

Black history is American history. John W. Jones’s name needs to be known. His story needs to be taught. His legacy needs to be honored.

Support Black History and John’s legacy with a donation to the John W. Jones Museum or by scheduling a tour during your next trip to Elmira. The entire operation runs on volunteer work, government grants, and fundraising efforts. With your help, the museum will be able to fulfill its dream of building a cultural and educational center on the property.